Moving Movements, History of Modern Painting, Chinese painting, a different history

Western European versus Chinese painting

The history of European painting is linked to European architecture. The walls of churches, palaces, castles and wealthier houses were increasingly covered with paintings. The discovery or rediscovery of oil paint (or oil paint on tempera), as well as the emerging wealthier bourgeoisie, brought about radical changes.

Modern painting emerged when painters painted in increasingly diverse styles, also reached the public and sold work. They opposed the precise painting of academics, who at the time mainly depicted landscapes, battles, hunting scenes and hunting grounds, portraits or religious subjects. Emerging in the period of Romanticism, academics painted very precisely their commissioned assignments in an idealized realism, close to standards, but when they painted for themselves or in preparatory work, coarser brush strokes and panache often appeared.

There was a real explosion of diverse styles from 1867 onwards (see previous pages). In order to better control and promote this art, the idea came to divide this evolution into movements. That was very artificial, and not correct. When Manet set up his own pavilion at the World Exhibition in Paris, after being rejected by the academics, he also invited other painters. The techniques of Renoir and Monet, for example, were very different from those of Manet. The subjects also differed greatly; not every 'impressionist' depicted the leisure time of the bourgeoisie. Pisarro, for example, mainly focused on the landscape, the farmer and the worker. Luce painted a demonstration smothered in blood as colorful & full of light as a landscape.

When galleries emerged and sales of this new painting became more successful, the idea arose to see this art as a growth, a development, an improvement. Evolution means change, but here it was framed as evolution towards a better world. That craze reached its peak under the philosophy of Theillard de Chardin, who saw the evolution of the world as a development of man, ever further in the direction of 'God'. This view was very Eurocentric. A blind eye was turned to the misery in the rest of the world, the history of exploitation and abuses under colonialism, and the European-American interests in the ongoing wars elsewhere. Although we can of course be proud of the European painting heritage and its legacy in other countries, such as the US, Australia and in fact everywhere, it is not a form of superiority. It also detracts from the fact that a very diverse artistic expression in Europe was the result of ceaseless efforts, social turbulence, growing self-awareness, tolerance plus broad interest, and often stubborn perseverance in difficult circumstances. What was vilified one moment was extolled later.

In this context, for example, the Western European painting evolution was often described as a transformation from figurative to abstract. However, that idea was demolished by the emerging surrealism. Originally abstract, it soon had very precise figurative painters such as Dali and Magritte, while others remained abstract, such as Miro. Max Ernst painted both.

Painting was done all over the world, painting existed long before man. In Europe, Neanderthals already had professional painters, and what was most often painted was the human body. But Homo Bergensis was also familiar with painting 100,000 years ago. Painting was widespread in the ancient world. South America has wall paintings with intact pigments, more than 6,000 years old.

Also in Asia, countries such as China, Japan, Korea, Vietnam... had a great history of painting, and we see how styles also evolved towards more diversity. Chinese painting, which could also decorate the interior of buildings, was usually painted with ink and pigments on silk or paper. Already hundreds of years before our style revolutions, China experienced incredible expansions in style, and at other times a return to restriction, depending on the political situation. Chinese painting is not divided into movements, like European painting, but into dynasties, up to modern times. This imperial legacy was therefore very decisive for the wealth of art and tolerance of diversity. The elegant styles, with fast and fleeting brush strokes that seem so modern to us, had their origins in religions such as Chan Buddhism (Zen Buddhism) or Taoism, and are rooted in the Chinese script, calligraphy. The importance of the brush strips, the speed of work and the search for their own techniques already happened in China when Europe was still in the Dark Ages, which is why we cannot limit ourselves here to the period 1800 to 1950.

The diversity of styles increased greatly in the Yuan period, and experienced a significant revival during the Ming dynasty. In the Qing dynasty came contact with European styles, which in turn led to new styles. The modern era was certainly not the most tolerant, with varying periods of tolerance to its complete absence.

The successive division into dynasties in the history of Chinese painting: Han Dynasty 206 BC to 220 AD, Six Dynasty Period 220-589, Tang Dynasty Period 618-907, Five Dynasty Period 907-960, Song Dynasty 960-1279, Yuan Dynasty 1271- 1368, Ming Dynasty 1368-1644, Qing Dynasty 1644-1911, Modern China from 1912.

The difference between European and Chinese painting has a lot to do with the medium. In Europe, watercolor was valued less, and oil painting was the main focus. China worked with ink and pigments on silk or paper. The material also influences the various styles.

click the thumbnails

Li Sixun, 651-716, Sailboats and pavillions (via comuseum.com)

Han Gan, ca 706-1783, Man herding horses (via wikipedia)

Li Zhaodao, Emperor Ming-huang's flight to Szechuan, ink & colour on silk (via wikipedia)

Luohan, after a set attributed to Gianxiu, carved in stone by Din Guanpeng (?) in 1757 (via metsuseum.org)

Shi Ke, Second patriarch in contemplation (via comuseum.com)

Dong Yuan, Riverbank (via comuseum.com)

Li Tang, ca 1066-1150, Wind in pines (via comuseum.com)

Guan Tong, Untitles, ink on silk (via mutualart)

Fan Kuan, ca 990-1020, Mountains landscape (via invaluable.com)

Fan Kuan, Sitting alone by a stream, 11th century, color on silk (via wikipedia)

Zhou Wenju (via artfox.com)

Ma Yuan, Egrets on a snowy bank (via comuseum.com)

Liang Kai, ca 1140-1214), Li Bai strolling (via comuseum.com)

Zhao Li, Auspicious cranes,

Li Tang (via pinterest)

Muxi Fachang, 13th century, Lao Tse, ink on paper (via terebess.hu)

Guo Xi, Old trees, Song dyn. (via comuseum)

Wen Tong, Landscape, ink on silk (via mutualart)

Attr. to Guo Xi, 1000-1090, ink and color on silk (via invaluable.com)

Attr. to Muqi Fachang, Returning sails off distant shore (via wikipedia)

Zhao Ji, Literary gathering, ink and colours on silk (via capacitea.co.uk)

Ren Zhong, Horses along the pine river (via montecristo magazine)

attr. to Qian Xuan, Basket of flowers, ink and color on silk (via christies)

Wen Zhengming, 1470-1559, Orchid and bamboo (via south.npm.gov.tw)

Xia Chang, 1388-1470, Bamboo, ink on silk (via sotheby's)

Ni Zan, Landscape, a gift to Ban Jun (via art.salon)

Chen Chun, (via comuseum.com)

Chen Hongshou, Lotus flowers and mandarin ducks (via comuseum.com)

Lü Yi, Sweet osmanthus, chrysanthenum and birds (via comuseum.com)

Lan Ying, white clouds and red trees (via comuseum.com)

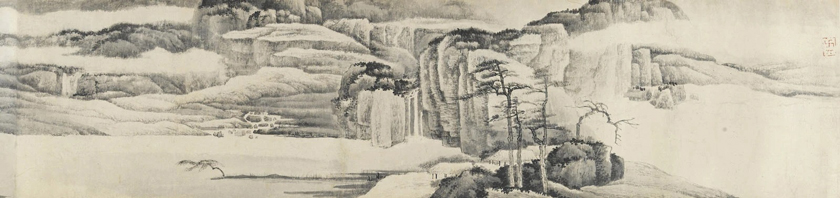

Wheng Zhengmin, Myriad of valleys (via comuseum.com)

Dai Jin, Boat returning amid wind and rain (via comuseum.com)

Chen Hongshou, 1598-1652, (via imgsrc.baidu.com)

Wu Wei, grapes (via archive.shine.cn)

Xu Wei, Flowers and plants

Attr. to Yun Shouping, 1633-90, Phoenix, ink and colour on paper (via christies.com)

Follower of Lü Ji, probably Ming-period, a pheasant, pair of ducks, other birds and flowers, watercolour on linen (via martelmaidensauctions.com)

Qiu Yin (via invaluable.com)

Zhu Da, 1626-1705, Two chicks, ca 1694, ink on paper (via artsmia.com)

Zhu Da, Egret on a stone, ink on paper (via sothebys.com)

Lang Shining, The qianlong emperor in ceremonial armor on horseback (via artsandculture.google)

Chen Hongshou, 1768-1822, Flowers in vase and tea set, ink and colour on paper (via christies)

Mirror-painting 19th century, one of a pair (via Christie's)

Xu Gu, 1823-1896, Squirrels, ink and colour on paper (via Christie's)

Ren Yi, 1840-1895, Two crows and wisteria, ink and colour on paper (via Christie's)

Hu Tiemei, 1848-1899, Rock, ink on paper (via Christie's)

Ren Yi (Ren Bonian), Zhong Kui (legendary demon queller), 1883

Gao Jianfu, 1879-1951, Autumn pleasures, 1915, ink and colour on paper (via christies)

Gao Qifeng, 1893-1933, Paradise flycatcher on pine tree, 1932, ink and colour on paper (via sotheby's)

He Tianjian, 1890-1977, Cloudy Xiajiang river gorge, 1944, ink and colour on paper (via sotheby's)

Lin Fengmian, 1900-1991, Opera figures, in and colour on paper (via christies)

Chang Shuhong, 1904-1997, Jiuncenglou (Mogaocaves), 1952 (via La gazette Drouot)

Zao Wou-ki, 1949, oil on cardboard (via artpro.com)

Zhang Chongren, 1907-1998, Eagle and pine, ink and color on paper (via invaluable.com)

Pan Yuliang, Lady in blue dress, 1942, oil on canvas (via shemakesarttoo.com)

Zhao Shao'ang, 1905-1998, Dragonfly by willows, 1968, ink and colour on paper (via sotheby's)

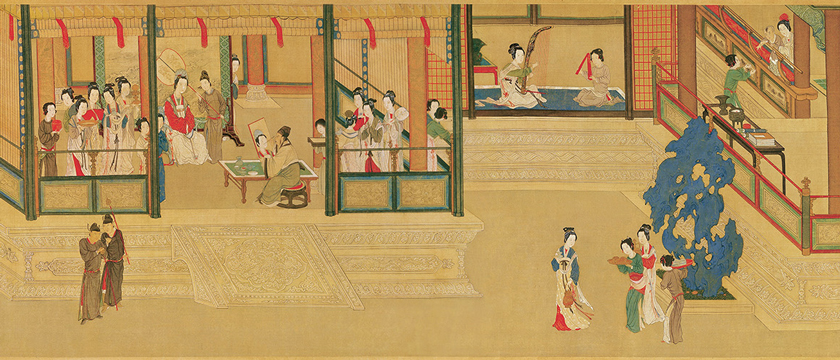

Zhang Xuan, 730-755, Court ladies preparing newly woven silk, copied by Huizong of Song (via comuseum.com)

Tang Dynasty 618-907

The Sui dynasty reunited China after 300 years of disintegration. The second Sui emperor waged unsuccessful wars and caused rebellion by making the population work too hard to dig a tunnel from North to South. The Tang built a much more sustainable state on the foundations of the Sui, the first 130 years being a very prosperous period. The Central Asian kingdoms paid tribute to China and Chinese culture influenced Korea and Japan. Chang'an became the largest city in the world, its streets were filled with foreigners, and foreign religions—including Zoroastrianism, Buddhism, Manichaeism, Nestorianism, Christianity, Judaism, and Islam—flourished.

This confident cosmopolitanism is reflected in all the arts of this period. The patronage of the Sui and Tang courts attracted painters from all over the empire. Yan Liben who became foreign minister was also a well-known figure painter in the 7th century. His duties included painting historical scrolls, notable events past and present, and portraits, including those of foreigners. He painted in a conservative style with delicate lines. His brother Yan Lide was also a painter.

The greatest brushmaster of Tang painting was the 8th-century artist Wu Daozi ( c.680-759), who not only enjoyed a career at court but also had sufficient creative energy to, according to Tang archives, so ' n 300 wall paintings to be executed in the temples of Luoyang and Chang'an. He painted with ink and left the coloring to his assistants. He achieved his sculptural effect only with ink lines. Figure painters who depicted court life in a careful manner, derived from Yan Liben rather than Wu Daozi, included Zhang Xuan (713-755) and Zhou Fang (c.730-800). The former's “Ladies Preparing Silk” has been preserved in a Song dynasty copy, while later versions of several compositions attributed to Zhou Fang exist. Eighth-century murals on royal tombs and Buddhist paintings from Dunhuang demonstrate the early appearance and widespread appeal of styles that these court artists later helped to canonize.

One of Emperor Xuanzong's favorite court artists was the horse painter Han Gan (706–783) The other great master of horse painting was Han Gan's early teacher and army general Cao Ba (c.704-770) Most later horse painters claimed Han Gan or Cao Ba, but the actual stylistic contrast between them was reported as early as Northern Song times as no longer distinguishable and is barely understood today.

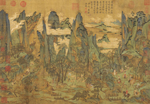

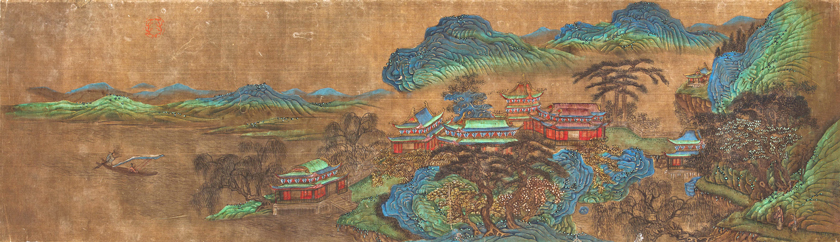

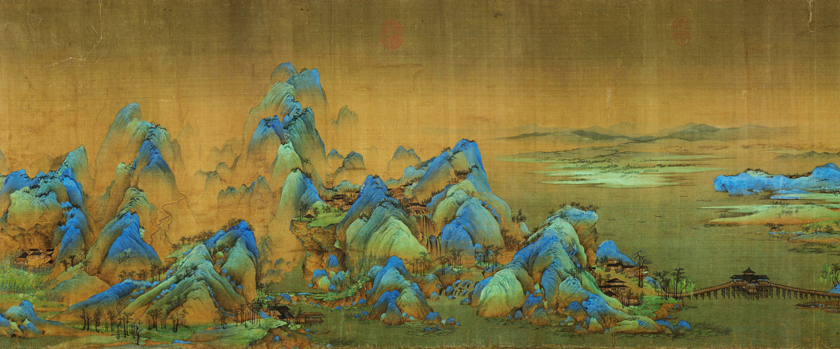

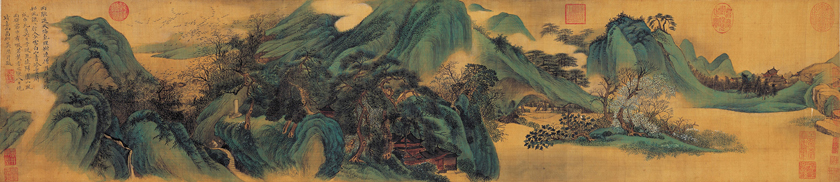

The more than three centuries of Sui and Tang were a period of progress and change in landscape painting. The early 7th and 8th century masters Zhan Ziqian (fl. late 6th century), Li Sixun (651-716), and his son Li Zhaodao (early 8th century) developed a style of landscape painting known as “blue-green landscape” or “ golden blue-green landscape”, applying mineral pigments to a composition carefully executed in fine lines for a richly colored effect. Probably related to Central Asian painting styles of the Six Dynasties period and associated with the paradisiacal landscapes of the Daoist immortals, this 'blue-green' type immediately appealed to the Tang court's taste for international exotic religious fantasy and bold fantasies.

The generally accepted founder of the school of scientific landscape painting is Wang Wei (701-761), an 8th-century scholar and poet who divided his time between the court of Chang'an, where he held official posts, and his estate of Wang Chuan , of which he painted a panoramic composition that was preserved in later copies. Of his Buddhist paintings, the most famous was a representation of the Indian sage Vimalakīrti, who became the 'patron saint', so to speak, of Chinese Buddhist intellectuals. Wang Wei sometimes painted landscapes in color, but his later reputation was based on the belief that he was the first to paint landscapes in monochrome ink. It was said that he achieved a subtle atmosphere by “breaking the ink” (pomo) in varied tones. The belief in his role as a founder, fostered by later critics, became the cornerstone of the philosophy of literary painting, which held that a man could not be a great painter unless he was also a scholar and gentleman.

More adventurous in technique was the somewhat eccentric late 8th-century painter Zhang Zao, who produced dramatic tonal and textural contrasts, as when he simultaneously painted, with one brush in each hand, two branches of a tree, one moist and blooming, the other withered and death. This new freedom with the brush was taken to its extreme by middle to late Tang painters such as Wang Qia (aka Wang Mo) and Gu Kuang, southern Chinese Taoists who “splattered ink” (aka Wang Mo) and Gu Kuang with characters other than "broken ink" on the silk in a manner reminiscent of 20th century "Action painters" such as Jackson Pollock. The purpose of these ink splashes was philosophical, religious and artistic. These techniques marked the emergence of a trend towards eccentricity in brushwork that was given free rein during periods of political and social chaos.

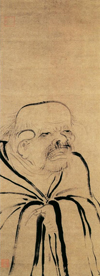

They were then employed by painters of the southern 'sudden' school of Chan (Zen) Buddhism, who believed that enlightenment was a spontaneous, irrational experience that could only be suggested in painting by a similar spontaneity in the brushwork. Chan painting flourished especially in Chengdu, the capital of the small state of Shu, where many artists went as refugees from the chaotic north in the last years before the Tang Dynasty fell. Among them was Guanxiu, an eccentric who painted Buddhist saints with a strange appearance and exaggerated facial features that had a strong appeal to members of the Chan sect. The element of the deliberately grotesque in Guanxiu art was further developed during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period by Shi Ke who was active in Chengdu in the mid-10th century. In his paintings, mainly of Buddhist and Taoist subjects, he attempted, in the Chan manner, to shock the viewer through distortion and roughness of execution.

Li Zhaodao, Temple in the pine forest, in and colour on silk (via mutualart.com)

Five Dynasties & Ten Kingdoms 907-960

With the fall of the Tang, China plunged into a state of political and social chaos. The north was ruled by five short-lived dynasties. The corrupt northern courts provided little support for the arts, although Buddhism continued to flourish until the persecution in 955 destroyed much of what had been created in the 110 years since the previous anti-Buddhist campaign. The ten independent kingdoms that ruled various parts of southern China, while not more steadfast, offered more enlightened protection.

Initially, the former Shu (capital in Chengdu) and then, for a longer period, the kingdoms of the Southern Tang (capital in Nanjing) and Wuyue (capital in Hangzhou) were centers of relative peace and prosperity. Li Yu, the last ruler of the Southern Tang, was a poet and liberal patron at whose court the arts flourished more brilliantly than at any time since the mid-8th century. Not only were the southern courts of Chengdu and Nanjing leading patrons of the arts, but they also began to formalize court sponsorship of painting by organizing a centralized studio with an academic component and granting painters an increased bureaucratic status – a policies that would be followed or adapted by subsequent dynasties.

Only a handful of painters worked in Northern China. The greatest of them, Jing Hao, who was active from about 910 to 950, spent much of his life as a hermit in the Taihang Mountains of Shanxi. No authentic work by him has survived, but texts and later copies show that he created a new style of landscape painting. Its crags, cleft by gullies and rushing streams, are boldly conceived and executed, mainly in ink, with determination and concentration, rising in rank to the top of the painting.

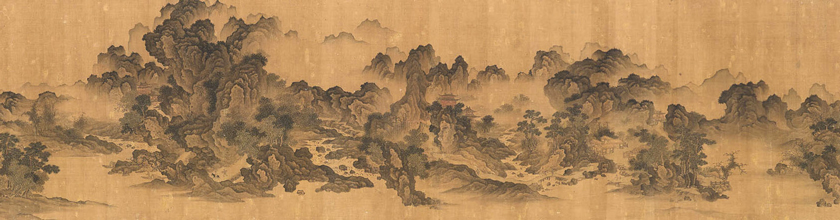

Jing Hao's importance lies in the fact that he both revived the northern spirit and created a type of painting that became a model for his successor Guan Tong and for the classical northern masters of the early Song period, Li Cheng and Fan Kuan. An essay on landscape painting, Bifaji (Notes on Brushwork), attributed to Jing Hao, explains the philosophy of this school of landscape painting. Painting was to be judged as much by its visual veracity in relation to nature as by its expressive impact. The artist must possess creative intuition and reverence for natural subjects, trained by rigorous empirical observation and personal self-discipline. Consistent with this, in all subsequent major schools of Song landscape painting, the artists had to rebuild their own regional geography, which served as the basis for their style, their emotional moods, and their personal visions.

Dong Yuan had an important post at Li Yu's court in Nanjing, he painted in broad strokes, almost impressionistically. The coarse brushstrokes (known as “hemp fiber” texture strokes), dotted accents (“moss dots”) and wet ink washes of his monochrome style are said to be derived from Wang Wei and suggest the rounded, tree-covered hills and humid atmosphere of the Jiangnan region (“south of the Yangtze River”). His brush is less firm than the northern ones, more spontaneous and relaxed. He and his successor Juran laid the foundation for two distinct traditions in Chinese landscape painting that continued into modern times. Their style became dominant in the Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties, favored by amateur artists. While the few figure painters in northern China typically recorded hunting scenes, the southerners, especially Gu Hongzhong and Zhou Wenju, depicted voluptuous, sensual court life under Li Houzhu. Zhou Wenju was known for his depictions of court ladies and musical entertainments, executed with fine line and soft, radiant colors in the tradition of Zhang Xuan and Zhou Fang.

Gu Hongzhon, The neight entertainments of Han Xizai, ink and colors on silk

Song Dynasty 960-1279

After a century of a unified China under 5 emperors, northern China fell to the Khitan tribe until 1125. From their new capital Bianjing, the new Song monarchs sought peace, bought off the Khitan, and ruled at home with unprecedented known tolerance, which greatly stimulated the arts. The Jurchens in the North seized power and subsequently conquered China and captured the imperial house. The new Jin dynasty took Beijing as its capital, what remained of the former court fled south in 1127, and chose Hangzhou as its new capital. They never tried to reconquer the north but opted for prosperity and flourishing arts. They continued to promote art and tolerance until the Mongols swept China clean in the 13th century and put an end to the rise of romanticism in art. In 1276, Hangzhou fell, the minister and the young Song emperor drowned.

The Northern Song was a period of reconstruction and consolidation. Bianjing was a city with palaces, temples and high pagodas. Buddhism flourished and the number of monasteries and temples increased again. The Song emperors attracted around them the empire's greatest literary and artistic talent, and something of this high culture was continued by their Liao and Jin successors. The atmosphere at the Southern Song court in Hangzhou, perhaps even more refined and civilized, was clouded by the loss of the north. Power and self-confidence no longer characterized southern Song art, instead it was imbued with an exquisite sensitivity and a romanticism that is sometimes poignant given the disaster that befell China in the 13th century.

This was the era of the dawn of archeology and of the first great collectors and connoisseurs. One of the most enthusiastic of these was the Northern Song emperor Huizong (r. 1100–1125), whose passion for the arts blinded him to the dangers that threatened his country. Huizong's refined antiquarianism reflects an attitude that became an increasingly important factor in Chinese art. It was said that the construction of his royal garden, the Genyue, nearly bankrupted the state, as giant garden stones brought in by boat from the south closed the Grand Canal for long periods. He was also the most distinguished of all imperial painting collectors, and the catalog of his collection (the Xuanhe Huapu, which includes 6,396 paintings by 231 painters) remains a valuable document for the study of early Chinese painting. Huizong also took the recent process of bureaucratization of court painting to new heights, with entrance examinations modeled on the standards of the civil service, with ranks and promotions like those of scholar-officials, and with regularized instructions sometimes offered by the emperor himself as chief academic . The favors granted to lower-class court craftsmen during the Song aroused the ire of aristocratic courtiers and spurred the rise of the amateur painting movement among these learned officials, which eventually became the literary mode of painting and most of Yuan (1206–1368), Ming (1368–1644), and Qing (1644–1911) history.

Fortitude and tolerance also allowed northern landscape painting to flourish. Li Cheng, successor to Jing Hao, was a scholar who painted the undulating earthen formations of the northeast with a "cloud-like" texture, in which inner layers of graduated ink washes were bordered by firmly brushed contours with scalloped edges. As with Jing Hao and Guan Tong, probably none of his original work has survived. Fan Kuan, from the early 11th century, began in the style of Li Cheng, turning directly to the study of nature and ultimately following only his own inclinations. He lived as a hermit in the mountains of Shaanxi, and one songwriter said that “his manners and appearance were stern and old-fashioned. He had a great love for wine and was devoted to the Dao.' In 'Travellers Among Mountains and Streams' the composition is monumental, the details realistic and the brushwork with a stippling style known as 'raindrop strokes', powerful and with a dense texture. Other northern masters of the 11th century were Xu Daoning and Yan Wengui.

The second half of the century was dominated by Guo Xi who became an instructor in the painting department of the Imperial Hanlin Academy. His style combined the technique of Li Cheng with the monumentality of Fan Kuan, achieving relief through shadows with ink washes (“cloud-like” texture), for example in “Early Spring.” His observations on landscape painting were collected and published by his son Guo Si.

As the monumental realist tradition reached its climax, a very different approach to painting was expressed by a group of intellectuals, including the poet-statesman-artist Su Shi, the landscape painter Mi Fu, the bamboo painter Wen Tong, the plum painter and priest Zhongren, and the figure and horse painter Li Gonglin. Su, Mi and Huang Tingjian were also the most important calligraphers of the dynasty. The aim of these artists was not to portray nature realistically, but to express themselves, to 'satisfy the heart'. In this amateur mode of scholar-official painting, skill was not valued as a characteristic of the professional painter and the court painter, but for the sake of spontaneity, clumsiness even became a virtue. Dong Yuan favored the 'boneless style', with only ink dots. This new technique influenced many painters, including Mi Fu's son Mi Youren, who combined it with a subdued form of ink splashes. Wen Tong and Su Shi were both devoted to bamboo painting, a demanding art form very close in technique to calligraphy. When Su Shi painted landscapes, Li Gonglin sometimes executed the figures. Li was a master of painting with baimiao (plain line), without color, shadow or wash. He brought the refinement of a scholar's taste to a tradition hitherto dominated by the dramatic style of Wu Daozi.

The northern emperors were enthusiastic patrons of the arts. Huizong was a calligrapher and a painter who mainly painted birds and flowers in the realist tradition dating back to Huang Quan and developed by later court artists such as Cui Bai of the late 11th century. Although meticulous in detail, his works were subjective in atmosphere, following poetic themes engraved calligraphically on the painting. For example in 'Five-colored parakeet'. Among the leading academics at the Huizong court were Zhang Zeduan and Li Tang, who fled south in 1127 and oversaw the restoration of the northern artistic tradition at the new court in Hangzhou. Although Guo Xi's style remained popular in the north after the Jin occupation, Li Tang's mature style came to dominate in the south. Li was a master of the Fan Kuan tradition, but he gradually reduced Fan's monumentality to more refined and delicate compositions and transformed Fan's small "raindrop" texture into a broader "axe-shaped" textural stroke that subsequently remained a hallmark of most Chinese court academies.

In the first two generations of the Southern Song, however, historical figure painting regained its former dominance at court. Gaozong and Xiaozong, the son and grandson respectively of the imprisoned Huizong, sought to support works that illustrated the ancient classics and traditional virtues. Subsequently, in the late twelfth and early thirteenth centuries, the primacy of landscape painting was reasserted. However, Li Tang's tradition was turned in an increasingly romantic and dreamlike direction by the great masters such as Ma Yuan, his son Ma Lin, Xia Gui and Liu Songnian, all of whom served with distinction in the painting department of the Imperial Hanlin Academy. These artists used the Li Tang technique, only more freely, and developed the so-called “great axe-shaped” textural stroke. Their compositions are often 'monoangular', showing a promontory in the foreground with a fashionably rustic building and a few stylish figures, separated from the silhouettes of distant mountain peaks by a vast and aesthetically affecting expanse of misty void.

Towards the end of this period, Chan or Zen Buddhist painting experienced a brief but notable flowering, stimulated by scholars leaving the decaying political environment of the Southern Song court for the monastic life practiced in the hill temples across the more of Hangzhou. The court painter Liang Kai had been awarded the highest order, the Golden Belt, between 1201 and 1204, but he put it aside, left the court and became a Chan hermit. The greatest of the Chan painters was Muqi, or Fachang, who restored the Liutong Monastery in the western hills of Hangzhou. The wide range of subjects of his work and the spontaneity of his style testify to the Chan philosophy that the 'Buddha essence' is the same in all things and that only a spontaneous style can convey moments of enlightenment. Chinese connoisseurs disapproved of the rough brushwork and lack of literary content in Muqi's paintings, and none appear to have survived in China. However, his work, and that of other Chan artists such as Liang Kai and Yujian, was collected and widely copied in Japan and formed the basis of the Japanese suiboku-ga (sumi-e) tradition.

Chan Buddhism has borrowed heavily from Taoism, both in philosophy and painting. One of the last great Song artists was Chen Rong, a civil servant, poet, and Taoist who specialized in painting the dragon, a symbol of both the emperor and the mysterious all-pervading power of the Dao. Chen Rong's paintings depict these fantastic creatures emerging from between rocks and clouds. They were painted using a variety of strange techniques, including rubbing the ink with a cloth and splashing it, perhaps by blowing ink onto the painting.

Chen Rong, Nine dragons, ink and colour on paper (via comuseum.com)

Wang Ximeng, 1096-1119, A thousand li of rivers and mountains (via shine.cn) This is the only work we know about this painter, who died at the age of 23. He spend six months on this work. Emperor Huizong discovered his talent and took him in the Imperial Painting Academy. He became the emperor's personal librarian and made this work when he was 18.

![]()

|

Attr. to Fan Kuan, Snowy scene of wintry tree (via news.cgtn.com) |

Liu Songnian, Lohan (via comuseum.com) |

Ma Yuan, Singing while dancing (via comuseum.com) |

Ma Yuan, 1160-1225, Ten thousand riplets on the Yangzi, ink on silk (via commons.wikimedia.org) |

Fan Kuan (via pinterest.com) |

Yuan dynasty 1271-1368

Since the invasion of the Mongols, the Chinese Empire was part of the Mongol Empire, which stretched from Korea to Hungary. The openness to other cultures was like never before, but the Mongolian dynasty was oppressive and corrupt. The last years of the short reign brought social and administrative chaos, especially because Chinese scholars were not trusted. As a result, art was little stimulated. The school of Buddhist and Taoist painting flourished by painting temple walls. Mongolian emperors, from Kublai to his great-granddaughter Sengge, collected ancient art and sponsored paintings, especially with themes of architecture and horses. The amateur painters of the educated class, in the tradition of Su Shien's Northern Song colleagues, dominated the Chinese painting standard for the first time. Eremitic subjects replaced the court scenes, art became more individual, and a stylistic gap emerged between the literary painters and the court painters, which would only recover in the 18th century. The literary painters started from a broader base and were inspired by very expressive calligraphy. Both style and subject had to reflect the personality and mood of the painter. A typical example of this is the simple orchid paintings of Zheng Sixiao.

Qian Xuan was a conservative flower painter before the Mongol invasion. At court he adapted his style and opted for Tang-style green and blue landscapes, with lots of calligraphy. Like many others, he had to trade his works for the livelihood of his family. Zhao Mengfu was a fellow citizen and follower of Qian Xuan, becoming a high-ranking official and president of the Imperial Hanlin Academy. During his official travels, he collected paintings by Northern Song masters that inspired him to revive and reinterpret the classical styles in his own way.

Other gentlemen painters who worked at the Yuan court maintained the more conservative Song styles, often surpassing their Song predecessors. Ren Renfa worked down to the smallest detail in his horse paintings. Li Kan carefully studied the bamboo varieties during his official travels and wrote a systematic treatise on painting them. Gao Kegong followed Mi Fu and Mi Youren in painting cloudy landscapes that symbolized good governance. Wang Mian, the plum painter, served anti-Mongol forces at the end of the dynasty.

The most lasting effect on Chinese painting came from the ancient painters, typified by individuality of expression, brushwork that reveals the inner spirit of the subject, or of the artist himself, and the suppression of the realistic and decorative in favor of simplicity. Four masters were considered the main exponents of this painting philosophy in the Yuan period.

Huang Gongwang, a Taoist hermit, was the eldest. His most respected and perhaps only authentic surviving work is the hand scroll 'Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains', painted with dynamic brushwork between 1347 and 1350. Expression was his goal, with a deep sense of unity with nature. Wu Zhen was a poor Taoist diviner, poet and master painter, like Huang Gongwang, inspired by Dong Yuan and Juran in landscapes and bamboo, painterly, with blunt brushwork, minimal movement and utmost tranquility. The third of the Four Masters was Ni Zan, a wealthy lord and bibliophile who was forced by crippling taxes to give up his estates and become a vagabond. As a landscape architect, he removed all images of people. He thus reduced Li Cheng's compositional pattern and, like Wu Zhen, achieved a sense of austere and monumental calm with the smallest means. He used ink, it was said, as sparingly as if it were gold.

Very different was the technique of the fourth Yuan master, Wang Meng, grandson of Zhao Mengfu. His brushwork was dense and energetic, derived from Dong Yuan, but confused and gray and therefore imbued with a sense of great antiquity. He often drew heavily on Guo Xi or what he considered Tang traditions in his landscape compositions, which he filled with scholarly retreats. Sometimes he also used strong colors, which added a certain visual charm and nostalgia to his painting.

Zhao Mengfu, Crossing rivers (via comuseum.com)

|

Mengfu Zhao (via invaluable) |

Wang Meng, 1308-1385, Ge Zhichuan moving to the mountains, ink and colors on paper (via chinaonline.com) |

Wang Mian, ca 1287-1368, Fragrant snow at the broken bridge (via comuseum.com) |

Qian Xuan, Squirrel on a peach branch (via wikimedia commons) |

Wu Zhen, Fisherman |

Ming Dynasty 1368-1644

Under the Ming dynasty, the empire recovered and even expanded. There was flourishing trade between Central Asia and the Chinese coasts, and via those coasts with foreign countries. The 15th century brought the highest prosperity and development of the arts, but in the last century of the dynasty there was much corruption at court and great dissatisfaction among scholars. Under the first Emperor Hongwu, many literary painters lost their lives due to the emperor's paranoid mind, which saw political conspiracies everywhere. The Ming emperors did not like the individualism of the literary painters and chose to make a bridge to the art of the Song dynasty. They treated the painters harshly and never united them in an academy. The remaining painters in the early Ming Dynasty preferred to stay at home in the south, and there was a wide gap with the court painters.

Court painters in the early Ming were, for example, Bian Wenjin and his successor Lü Ji, who continued bird-and-flower painting. Nevertheless, southern landscape painters became increasingly popular, such as Li Tang, Ma Yuan, and Xia Gui. Dai Jin, under the fifth emperor, lived at court under great jealousy from court rivals, burdened with intolerable restrictions. He was inspired by calligraphy and was therefore much freer in his brushstrokes.

The Zhe school of painting included painters who moved from the Hangszou region in the south to Beijing, fleeing autocratic politicians, characterized by eremitic Taoist themes and eccentric brush strokes. Wu Wei's drunkenness at court was forgiven because of his genius with the brush. Few amateur painters rose to higher positions at the early Ming court. Wang Fu survived a long period of exile and returned to the court as a caligrapher. Other official court scholar-painters in the Yan tradition were the bamboo painter district in the mid-15th century.

The Wu District of Jiangsu, in which Suzhou is located, gave its name to the Wu school of landscape painting, which was dominated in the late 15th century by Shen Zhou, a friend of Liu Jue. Shen Zhou never became a civil servant, but devoted his life to painting and poetry. He often painted in the manner of the Yuan masters. His work is unsurpassed in all Chinese art for its humane feeling. The soft and unpretentious figures he introduced give his paintings great appeal. Shen Zhou mastered a wide range of styles and techniques. He also became the first to establish a flower painting tradition among literary painters. He was followed with even greater technical diversity by Chen Chun, Xu Wei in the later Ming, and by Zhu Da and Shitao in the early Qing. Their work sparked the revival of flower painting in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

Wen Zhengming was a student of Shen Zhou, painter and caligrapher, he refined styles from the past. Students like his son Wen Jia and his cousin Wen Boren transcended the work of many lesser late Ming painters, who degenerated into a precise and artificial style. Three of these Suzhou masters had developed a different, but also very good combination of styles at the beginning of the 16th century, and were very popular: Zou Chen, Qiu Ying and especially Tang Yin, who became very mythologized in later times. In the following generations, the genres between amateurs and professionals blurred.

In the early 17th century, some began to show the influence of Western art, engravings and paintings brought to China by Jesuits, such as Wu Bin, Zhang Hong and Lang Yin. They may have been responsible for the first figure revival since the Song, such as Chen Hongshou and Cui Zizhong, and they also introduced perspective, shading, more distortion and color saturation. In Chen and Cui's work the grotesque and satire are also striking. The orthodoxy was broken to the extreme by Xu Wei with his explosive paintings of flowers, plants and bamboo, total mastery of brush and ink.

The critic and painter Dong Qichang considered this explosion of styles a sign of decline and increasing corruption during the late Ming. His own landscape paintings were nevertheless original and quite daring.

Qiu Ying, Spring morning in the Han palace (via comuseum.com)

|

Wheng Zhengmin, Old trees (via comuseum.com) |

Xu Wei, Flowers and bamboos (via comuseum.com) |

Zhu Da, Lotus and ducks(via comuseum.com) |

Qiu Ying, The emperor Guangwu fording a river, ca 1534-42, ink and colors on silk (via artandobject.com) |

Guiseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining in Chinese), 1688-1766, Myriad longevities in an everlasting Spring, (via theme.npm.edu.tw) |

Wu Wei, plants

Guo Zhongshu, 15th century, Living in the mountains, ink and colour on silk (via christies)

Qing Dynasty 1644-1911

The Manshoe conquest of China was not a threat to Chinese painting, they were imitating Chinese customs even before the invasion. The first emperors supported the Chinese scholars. They had an extravagant taste in art, but at the same time they were both politically and culturally conservative. These compensated for each other and as a result, even the most eccentric painters showed lavish decoration, excellent techniques and conservatism. In the 19th century, painting stagnated as a result of increasing Western power. The Manchu rulers' dual attraction to unbridled decoration and to orthodox academicism characterized their patronage at court.

There they favored artists such as Yuan Jiang, who during the Kangxi reign combined with great decorative skill Guo Xi's model with the mannered distortions that had emerged in the late Ming in the 1950s, partly as a result of Western art. Court painter Jiao Bingzhen, applied Western perspective to his illustrations of the text Gengzhitu (Rice and Silk Culture), which were reproduced and distributed in the form of wood engravings in 1696

In the mid-18th century, Guiseppe Castiglione (Chinese Lang Shining) produced a Sino-European technique that had significant influence on court artists such as Zou Yigui, but he was ignored by literary critics. His depictions of Manchu hunts and battles provide a valuable visual record of the time.

The Manshoe emperors ensured that the conservative painters in the scholar-amateur style, such as Dong Qichang and his successors, were also well represented at court, thus putting an end to the struggle between amateurs and professionals that had arisen in the Song Dynasty and was so important in the Ming Dynasty. The Qianlong Emperor was the most energetic royal art patron since Huizong of the Song. He built and cataloged an imperial collection of more than 4,000 pre-Qing paintings and calligraphies, although he sometimes favored recent forgeries rather than originals. He made inferior caligraphic additions and several court stamps to many masterpieces. The Qing's conservatism was reflected in the sooty compositions of their painters, with little variation or imagination. The fluidity of their brush strokes became the only basis for appreciation, as we see with the 'Six Master' and their successors.

Wang Hui was a dazzling child prodigy with successful amateur-style forgeries of old masters. The decline of his style reflected the decline of painting in Qing literature due to the lack of innovation. Wang Yuanqi was the only one of the six masters who lived up to Don Qichang's efforts to creatively transform the styles of the past. Wang Yuanqi rose to a high position under the Kangxi Emperor as chief compiler of the Imperial Painting and Calligraphy Catalogue.

Another group of painters had no Manchou support, with a small following in the second half of the 19th century. They marked a triumphant but short-lived moment in the history of literary painting. They rejected the authority of the Mashoes and opted for a poor hermit life, where they had to exchange their works for their livelihood. For example, Gong His most impressive work is his 'Thousand peaks an Myriad Ravines'. He belonged to the famous Eight Masters of Nanjing.

Kuncan became abbot of a Buddhist monastery and painted melancholic landscapes. He used the densely tangled brushwork of Wang Meng (Yuan). Another individualist painter was Hongren, famous landscapes of the nearby 'yellow mountains'. The group of artists of the Anhoui school strove for a serious coolness in a spare, dry linear style: Xiao Yuncong, Zha Shibiao, and Mei Qing, among others. In the 17th century, the Anhoui style became very popular among wealthy collectors, and owning a Hongren painting was seen as the mark of the knowing connoisseur.

Among individual masters, two Buddhist artists from the deposed and decimated Ming imperial family left behind the most lasting legacy of all. Zhu Da (also called Bada Shanren), feigned a period of madness and stupidity, he painted in an eccentric style in extremes, wet and wild alternating with dry and withdrawn use of brush and ink, menacing birds and fish, with strange and ironic glances, structurally interwoven rocks and vegetation in a composition without precedent.

Zhu Da's cousin Shitao was secretly raised in a Chan Buddhist community. He then wandered around the Yellow Mountains before settling in Yangzhou. Later in life he made his royal descent known and turned professionally to painting. His style was very free and unconventional, with bold use of color. He mocked traditionalism, he thought his method was not a method but nature itself, with spontaneous and seamless brushstrokes. Shitao is often grouped with seven others he inspired, called the “eight eccentrics,” including Zheng Xie, Jin Nong and Huang Shen. Their extreme stance contrasts with the Qing's growing scholasticism. In the early 18th century they were supported by wealthy merchants in Yangzhou. The art of Zhu Da and Shitao only became truly influential due to the emerging individualism in Shanghai at the end of the 19th century. In the 20th century they had a great influence on Chinese painting.

Wu Li, 1632-1718, Green mountains and white clouds (via comuseum.com)

|

Lang Shining, 1688-1766, Brocade of Spring (comuseum.com) |

Hongren, 1610-1664, Cinnabar house in the distant mountains, 1656 (via amis-musee-cernuschi.org) |

Zheng Xie (Zheng Banqiao), 1693-1766, Bamboo, ink on paperboard (via invaluable) |

Huang Shen, 1687-1772, Lin Bu appreciates the plum flower (via wikipedia) |

Leng Mei, Reading lady (via Pinterest) |

Gong Xian, Studio in the mountains, ink on paper (via mutualarts)

|

Zheng Jilin, late Qing dynasty, Reading scholar, ink and colour on paper (via sotheby's) |

Hua Yan, 1682-1756, Appreciate the Autumn season, ink and colour on silk (via christies)

|

Bada Shanren, 1626-1705, Heron and lotus, ink on paper (via christies) |

Anonym, painting of a lady, 1820-1911 (end of qing dynasty), ink and pigment on paper (via bonhams) |

Shen Quan, 1682-1760, Phoenix, ink and colour on silk (via christies) |

|

Anonymous, Daoist figures, late Ming early Qing, ink and color on silk (via Christie's) |

Leng Mei (via chinesestylefinds) |

Anonymous, 19th century, Lady holding an orchid, oil on paper (via bukowsky's) |

Anonymous, Duanwu festival, Qing dynasty, ink and colour on silk (via Sotheby's) |

Li Shan, 1686-1762, Broad beans and insects, 1734, ink and colour on paper (via Christie's) |

Modern China from 1912

Painting in China reflects the influence of the West and, as elsewhere, the political, military and economic struggles, including the war with Japan (1937-45), the subsequent civil war that resulted in the Chinese Republic in 1949, and the rapid economic changes of the 20th and 21st centuries. The first innovations came from Shanghai, after it was forcibly opened to the West in 1842 and gained a new wealthy customer base. By 1850 there was a distinct regional style led by Ren Xiong, his popular successor Ren Yi, and his successor Wu Changshuo. More than the old landscape painters, they emphasized figures, birds and flowers, with more stylization and decoration instead of refined brushstrokes. Their style reached Beijing in the 20th century, especially through Wu Changshuo, with painters such as Chen Shizeng or Qi Baishi.

The first modernization came from Japan where Western and Japanese characteristics were mixed, such as in Nihonga painting. The first Chinese painters with this Japanese influence included Gao Jianfu, his brother Gao Qifeng, and Chen Shuren. Gao Jianfu studied in Japan for four years and later took part in the uprisings in Guangzhou (Canton) that led to the republic. Chen and the Gao brothers created a new national painting, which later gave rise to a new Cantonese style, the Lingnan, with European and Japanese characteristics. That style did not open up a new perspective, but continued to flourish in Hong Kong for a long time with artists such as Zhao Shao'ang.

Western-style art education started in 1906, the 'Shangai school of art' was founded in 1911 by sixteen-year-old Liu Haisu. Later came public exhibitions and the use of models in the classroom.

In the 1920s, more and more young artists moved to art centers such as Japan, Germany and Paris. Liu Haisu was attracted to Impressionism. Lin Fengmian felt more inspired by the Fauves, in 1928 he became director of the National Art Academy of Hangzhou and advocated a synthesis between Western techniques and Chinese expressiveness. Xu Beihong, head of the art department at Nanjing University, eschewed European modernist movements in favor of conservative academic styles. His monumental figure paintings served as the basis for social realist painters after the communist revolution of 1949.

In the 1930s, most artists advocated joining modernism. Exceptions were Qi Baishi, who continued to paint in the Shanghai style, and Huang Binhong, grand master of the ancient tradition.

In 1942 the foundations for aesthetics were laid for the years to come. Art had to be of and for the people, and positive towards the communist party, without satire. 'Art for art's sake' was severely condemned.

As a result of the Sino-Japanese War, there was a veritable exodus of artists from Eastern China to the then capital, Chongqing. That brought a great artistic mix. However, everything was thwarted by the communist party, which placed all artists' associations under the propaganda service, with strict control over publications and elimination of the commercial art market.

In the 1950s, oil paintings and woodcuts were preferred. The conservative leaders of academies died one after the other, and young artists who replaced them were more willing to compromise. Li Keran created a new naturalism in the traditional medium. A leading figure painter was Cheng Shifa who painted politically minded images of Chinese minority peoples in the Shanghai style.

While the early 1960s marked a moment of political relaxation for Chinese artists, the Cultural Revolution of 1966–1976 brought unprecedented hardships, characterized by forced labor and lifelong imprisonment. The destruction of traditional arts was widespread, especially in the early years. Only the arts sanctioned by a military-led apparatus under the rule of Mao's wife, Jiang Qing, could flourish. The party's propaganda dictates became increasingly strict and anonymous as collective works. In the early 1970s, when China first reopened Western contacts, Premier Zhou Enlai attempted to restore government patronage of the traditional arts. As Zhou's health deteriorated, traditional arts and artists suffered again under Jiang Qing, being publicly labeled and punished as "black paintings" after the 1974 exhibitions in Beijing, Shanghai and Xi'an.

The death of Mao and Maoism after 1976 brought a new and sometimes refreshing chapter in the arts under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping. The 1980s were characterized by declining government control and increasingly daring artistic experimentation. 1979 saw the rise of cubist and other Western styles, nude figures in the murals, influential private exhibitions and the rise of a truly realistic oil painting movement, which swept away the artificiality of socialist realist propaganda. The 1980s saw a revival of traditional Chinese painting, with the return of previously disgraced artists including Li Keran, Cheng Shifa, Shi Lu and Huang Yongyu, and the emergence of new talents such as Wu Guanzhong and Jia Youfu.

After 1985, the once threatening traditional style painting began to seem to the government a safe alternative to the avant-garde. In the last months before the imposition of martial law in Beijing, June 1989, an exhibition of nude oil paintings from the Central Academy of Fine Arts at the Chinese National Gallery and an avant-garde exhibition of installation art, performance art and printed scrolls took place, mocking the government. They both attracted record numbers of visitors. The latter was closed by the police, and both exhibitions were eventually denounced for lowering local morale and precipitating the tragic events that followed in June 1989. New restrictions on artistic production, exhibitions and publications followed.

The arts in China today enjoy greater freedom than in the past half century, that is undeniable. But that freedom has limits. The reins of artistic freedom in China are much older than the restrictions imposed by Mao and his heirs. The belief that the individual must give loyalty and responsibility to the group, be it the family or the state, is deeply rooted in traditional Chinese culture and has also limited traditional painting. The overall goal is to achieve social harmony. Only when that harmony breaks down, for example with the decline of a dynasty or unbearable oppression, does individualism speak with a stronger voice.

This brief history of Chinese painting was compiled mainly with comuseum.com as source

Pan Tianshou, Fowl and rocks, 1950, ink and colour on paper (via bonhams)

|

Gao Jianfu, 1879-1951, Bird perching on rock, 1918, ink and colour on paper (via sotheby's) |

Li Fengmian, 1900-1991, seated lady, ink and colour on paper (via christies) |

Gao Qifeng, 1893-1933, Ferrying in the mist (via Alain Truong) |

Chang Shuhong, 1904-1997, Two sisters in the parlour, 1936, oil on canvas (via westbund.com) |

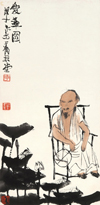

Li Keran, 1907-1989, Scholar admiring lotus, 1948, ink and colour on paper (via sotheby's) |

Su Tianci, Early Spring of Fuchun river, 1979, oil on paper on panel (via mutualart)

|

Fu Baoshi, 1904-1965, Warriors on the night mars, 1945, ink and colour on paper (via alaintruong.com) |

Hu Shanyu, 1909-1993, Ploughing, oil on paper (via christies) |

Zao Shao'ang, 1905-1998, Bird on reed, 1969, ink and colour on paper (via sotheby's) |

Pan Yuliang, 1895-1977, Nudes and masks, 1956, ink and colour on paper (via christies) |

Pang Xuncin, 1906-1985, Girl under a tree, ca 1940, ink and colours on paper (via museecernuschi) |