Moving Movements, History of Modern Painting, Preview and Survey

This work sketches the revolutionary changes in European painting, from the end of the 18th century until the Second World War. A lot of books on the history of art give a wrong idea: they sum up some movements, which follow a clear evolution. For this purpose they often do some juggling with dates and keep silence about quite a lot of very good painters. In this work we start from data, we describe shortly on how many different ways painters work beside each other in that particular period. We discover how the revolution starting in the second half of the 19th century is mainly a revolution in versatility and individuality. Symbolism, for example, was growing in popularity, has given us a treasure of high quality and various works. Nevertheless symbolism is not mentioned in a lot of books on history of art!

To be able to give a description of the periods, we have to hold on to the concept of "movements", but we keep in mind this is an artificial classification with its restrictions. An exposition which shows what was painted in a particular year would give us a far better idea of painting in that period, then an exposition of a particular movement or painter. This work wants to give you a more representative idea of the creativity and originality of human being, as well as the desire to create beauty. We also want to correct the wrong concept on history of art

as a result of the pernicious school education or misleading art books. Of coarse there also exist books with history of art and expositions which give a true idea of this subject, with attention for correct dates and mutual comparisons, also with other branches of art and other facets of culture.

This essay works chronogically, in this way the oeuvre of many artists are showed next to each other. We

start with the first changes in England and France between 1840

en 1870; France is classified a second time in the time before or during the first impressionist works. From there we treat the subject in decades.

Modern art from ages ago

click the thumbnails

Punu Lumbu Mask

Yup'ik Mask Alaska

Huichol Shaman Wood Mask

Ornamental Endpiece

from a Qu'ram Manuscript

Tibetan Mandala Sand Painting

Old Photo from a

Navajo Sand Painting

Prehistoric Cave Paintings

Lascaux France

Prehistoric Cave Paintings

Alta Norway

Tupa Inca Tunic ca 1550

Rada Krishna

17th Century Painting

Guardians of Day and Night

Han Dynasty

Fresco Thera Greece ca 1600BC

Old Indian Tantra Painting

Cloth tunic, Inca

(AD 1400-1532),

Lima Region, Peru

Rhodian orientalising plate

"Rhodian plate", circa 600 BC

Ancient Greek geometric art box in the shape of granaries, 850 BC

Painted Hauses Sirigu Africa

Painted Hauses Slowakija

Isis 1360 BC

Roman Wall Painting from

Room

of the Villa of P. Fannius

Synistor

at Boscoreale

Woman playing a Kithara

Same Kithara in this painting from Gustave Moreau 19th century

Jheronymus Bosch

Fragment from

The Garden of earthly Delight

ca1505-15

François de Nomé, 1593 - 1620, The Tomb of Solomon

Lucien Adrion, 1889-1953, The Dinner of Artists making up by Monsieur et Madame Paul Petrides, 1937

Abstract painting flourished in Europe since the beginning of the 20th century, but it was absolutely not original. It was the first time it was worked out profoundly. The movement of surrealism began later, after the rise of abstract art. The figurative surrealists were recognised with aversion, because their precise figuration destroyed the idea of abstract art as finality. But the public liked it, as they also started to like the former symbolists, Klimt en Khnopff.

| The taste of the public is no reference for quality, because a lot of artists became forgotten. Take Monet, Manet, Degas, Renoir, Van Gogh, Gauguin,

Picasso, Magritte, Ernst, Dali, Kandinsky, Klimt, and you have a minor part of the renovators between 1850 and 1950, but already about 90 percent of the artists of which books are made or expositions hold. Each painter has his own, specific style, common styles do not exist. Therefore it is better to speak of movements. The classification in isms is invented to get a better idea of the flood of changing and renewal. It is always subjective to classify certain artists to a specific movement; books deal with it in very different ways. Painters sometimes start with a group, but such a group often doesn't live long, and other painters, working with the same basic characteristics, never really belonged to that group. Those painters are classified in this movement, based on the period they painted, on mutual contact or friendship, on their presence on meetings, in magazines, on expositions, and so on, or just because of some style characteristics. Movements and style descriptions can only give a vague description and place. Furthermore many artists do not belong to a certain movement, or do belong to a particular group in a certain period, in another period to another movement. Nevertheless to get some insight on the creative outburst, we are obliged to use these movements or isms as a starting point. We restrict ourselves in the number of isms; terms as naturalism, luminism or orphism are avoided on purpose in this essay. |

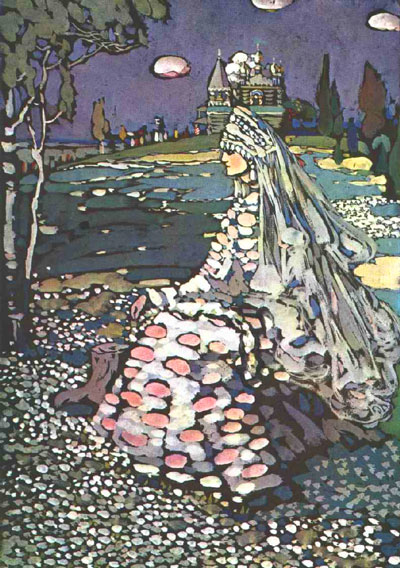

Kandinsky, Russian woman in a Landscape, 1905, before his abstract and even before his fauvist period |

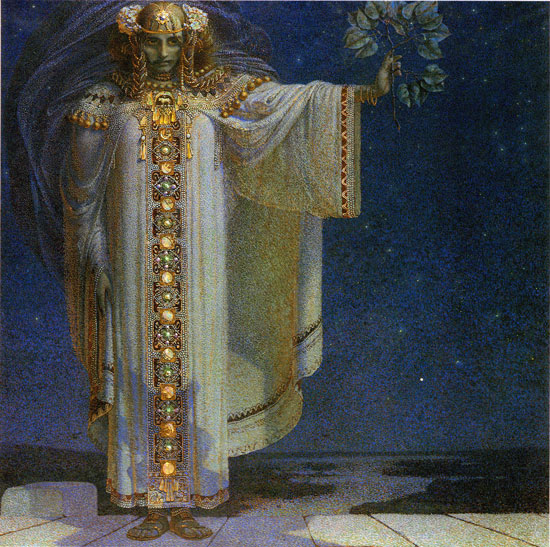

Vitezlav Karel Mazek, The Woman Prophet Libusa |

A basic problem in this classification system is that some movements are determined based on their subjects, on what was painted, while others were based on their technique, the how. Surrealism, symbolism, romanticism and abstract art belong to that what-category ("abstract" also, because it restrict what is painted to the non-figurative). Impressionism, naive art, expressionism en cubism belong to the how-category. The result is that a certain painting can belong to two movements, one of the what-category and one of the how-category. On the left is an example of "The Prophet" by the Czech Mašek, symbolist by subject, pointillist by technique. |

Moreover, some artists did paint sometimes symbolist subjects, and other works to nature. A clear example is Gauguin, with sometimes very symbolist works, but also with scenes from nature or daily life. Based on his technique he belongs to the Nabis (he was one of the founders of the original Breton group, but left them soon), or he is classified as Neo-Impressionism, a collective noun for those who deviated from academism as well from impressionism in that period.

Not only "authorities", "experts" and critics wanted that classification in isms, sometimes also artists wanted it, as for example Kandinsky. He had profit in classifying himself as an indispensable link in the so called evolution of painting. Also for the sales those isms were a welcome tool, to convince the candidate sellers how good and original the artist was, and how emancipated from academism.

A lot of painters were bitter by the incomprehension of the academics to renewal, but they were intolerant themselves to otherwise orientated pioneers. They only recognised those who followed more or less their way of working. Some artists do even not accept the last, they experience each resembling painter as a concurrent or a threat.

Romolo Romani, Immagine, 1908 |

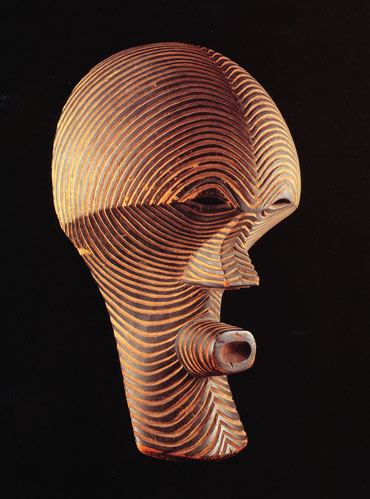

Also outside Europe people expressed themselves according to their culture and traditions. Their environment prescribed the standards they had to hold on to. The culture also prescribes the freedom an artist has. Old African sculptures and masks are very expressive and do not want to look exactly as the human face. Compared to the ancient European sculpture, it looks quite revolutionary, but even they are working within the directives of their community. Already long ago certain cultures in America and Africa painted their houses with totally abstract patterns. We also do find abstract art in very old cloths. Maybe abstract art is older in humanity then figurative! In the Islamic art abstraction flourished, because the religion forbids the figurative. By the same reason the Rosicrucian's painted already abstract in Europe in the 17th century. |

The existence of canvas is not a measure for painting either, canvas is a typical western product. Canvas goes together with architecture, where even walls do ask for decoration. There can be painted on the wall, but a hanging canvas is changeable. Japan, which also has architecture with straight walls, also has an extensive history of painting: on panels, sliding doors, folding screens, scrolls... The ancient Greek painting is not only on walls, but also on vases. It is like a painting on a bowed surface. In a lot of ancient cultures we notice realism, stylization, abstraction, expression, surrealism and naivety.

In our history of painting they succeeded each other chronologically, but other cultures prove this is not the only possible evolution. It is specific for our western culture. Copyright for the text of all pages of this History of Modern Painting: Johan Framhout; text written in 1990-92; revisionned and put on the internet in 2005; translation in English 2012 |

Back to the future: two examples of old African masks (Congo). Can it be more modern?

|